Baths are for the filthy English!

When I heard David Lynch had died, I was staring at this page before it had words on it. Before the sad, sad news was announced with a jaunty lilt on BBC Radio 6, I was feeling anxious that I’d missed last week’s promised substack-thingy, and it was getting in the way of my first thought. But with David Lynch in my head, it all spewed out willy-nilly.

I saw him walking down the Croisette in Cannes in 2002 , a cloud of cigarette smoke behind him. I think he was on the jury that year. He was paler than pale with a fag hanging out his mouth and a shock of white hair like a Japanese caricature of a unicorn’s mane… for a second, I thought he might be Jim Jarmusch, but David Lynch’s hair has an invisible wind that blows it to the left. He stood out among the high-definition Hollywood Riviera tans like he was in black and white. Lynch walked quickly to avoid chat from acolytes on the street. I was a big fan, not an acolyte. I saw myself, see myself, arrogantly, as a fellow traveller on The Ship of Fools. I was happy just to see him across the street and not walk over and stop him in his path and say something clever like, ‘I think you’re brilliant’ – just knowing the likelihood of blood pumping through his veins was satisfying enough, like spotting a kingfisher in February. So, I followed him down the street at a safe distance - being Jeffrey Beaumont - I kept a non-pervy distance and then lost him in The Majestic.

I have previous with this. In New York in 1982 I shook the hand of Ornette Colman pissing in the toilet of the Blue Note jazz club; he’d barely put it away, let alone wash, before I grabbed his hand and shook it. ‘That was not cool’, he said.

And there was the time I knocked on Stanley Kubrick’s caravan to give him a short film script I’d written on the set of Full Metal Jacket. ‘What do you want me to do with it?’, he said.

I waited too long just looking at him, sensing it was a reasonable question, just one I hadn’t considered.

‘Read it?’

He looked at me without any change of expression and closed the door. I could see Mathew Modine and Vince D’Onofrio inside, looking interrupted.

There are more of these too painful to paint here.

To call David Lynch ‘Oscar-nominated’, that the headlines and obits churned out today, is silly. Oscar-nominated (not won, for fucks sake) describes perfectly what he was up against. And what he wasn’t… although I don’t know the man, only how he walks. Lynch looked like an artist who was true to his thinking, problem-solving, and obsessions with everything he did in film, in words, in pencil, and in paint. And like all good artists, not all his work was good. Work is work in progress, good and not so good like life: it looks forward, then goes back and forth again, edging to the essence, to the spark of life in consciousness that an audience might recognise in the moment or many years later on the loo, or in a conversation with a nobody about nothing when one’s eyes glaze over, and Nobody asks if you’re okay, and you tell them it’s nothing, but actually it was everything, and your life just changed in front of Nothings eyes. .

David Lynch was true and sincere. He was good to us.

Here’s a letter to David Lynch (not a tribute).

Dear David Lynch,

This letter is not a eulogy, you’ve had too many of them by now. It’s hard to think of you dead, that’s all… this letter is more about me. sorry.

I missed my Substack post last week. I promised to deliver a weekly episode on the restoration of a documentary I made years ago, My Macondo, in the light of the Netflix release of One Hundred Years of Solitude, and I fucked up. I failed to deliver. The series claims to be an adaptation of the famous novel. They recreate the town of Macondo and everything that happened in it, in shiny digital mesmeric brilliance (I still can’t get past the first ten minutes; I don’t know why, but I suspect you do).

My film is about Macondo in a roundabout way. But I doubt you saw it when it came out in 1990 because your Wild at Heart was released the same year, and you must have been very busy.

I heard a rumour you were in Cuba when our film was screened at the Havana Film Festival in 1991. I don’t know if that’s true?

\What a time we had - but I missed a party where Fidel (Castro) and Gabo (Garcia Márquez) cooked pancakes for Angolan medical students from the International Medical School. Fidel wore a cowboy hat, apparently. I suppose I’ll never know if you were there or not now that you’re dead… but you made almost anything possible in your work like Gabriel Garcia Márquez could, so let’s leave that gate open. Let me know, when you can.

There’s something edgy about the Substack deadline. The thing about promises and deadlines generally is that real life gets in the way of writing, and I’m learning to let life take priority. Was it like that for you?

On the morning I set aside to write this thing, I lifted an 18th-century marble bust of a Jane Austin lookalike (too plump and thick-necked to be Austin) out of the garden of my old house that my ex-wife had just sold; there was an immovable beast of a French armoire too, three 19th- century paintings of Mount Etna painted by sailors who couldn’t paint but felt the power of the earth, like you did; a plastic bag of VHS tapes, some colourful window boxes that my dad’s alleged lover sold him in the early ’70s (she taught me how to fry an egg, but I’ll save that story for the therapist - I hear you stopped doing therapy because you thought it hindered your creativity… I hope it doesn't do that for me. I quite like it. Shit).

It was the Jane Austin bust that shredded the tendons in my right ankle that sent me to A&E in Halifax – a fabulous, beautiful town in Yorkshire with societal issues (a proud shit hole).

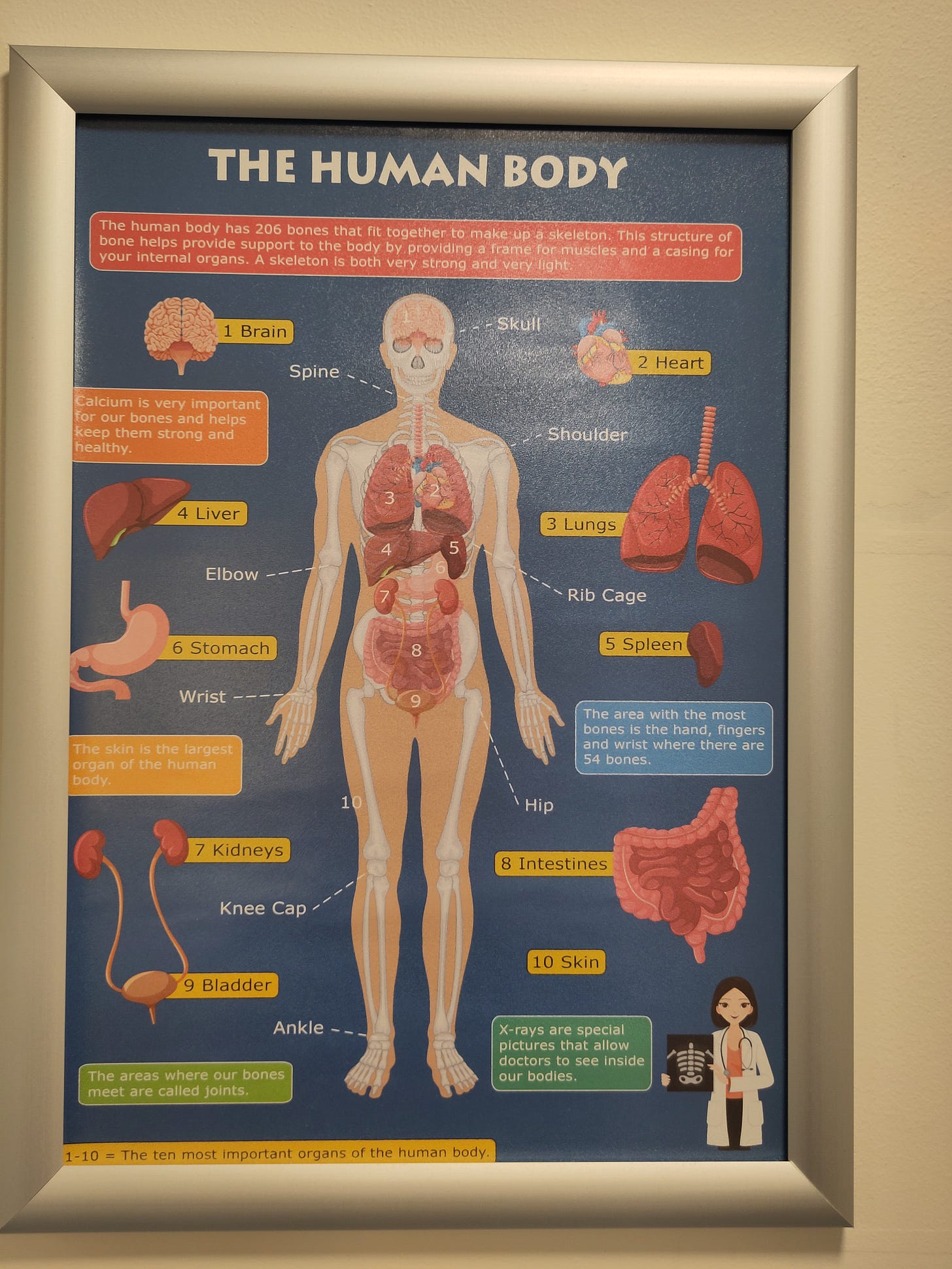

It was an experience now etched in my brain. it was like a grotesque opera about all that is monstrous and incredible beyond belief – you would have loved it – the poor, the mad, the lost, the innocently injured and the self-harmed, the nearly dead and betrayed jumbled in with saints and angels: doctors, nurses and health care support workers they blessed us injured reprobates with care and what felt like genuine concern. They gave a shit beyond what they get by the hour… there was the poster on the wall in the kid’s section of the x-ray room, pointed out to me by an overweight, six-foot-tall eleven-year-old whose front teeth had been knocked out by a vape shop owner who’d smashed his face on the bonnet of a parked police car – he said, blood spitting from his mouth, ‘we don’t have seven kidneys, do we?’

‘But we do have one brain’, I said. And we agreed on that…

And as the Halifax spice mellowed, as the hours went by waiting for the Doctor to determine the outcome of my ankle x-ray, I got a message from my daughter (just turned 30) who bashed her leg, the same leg as me, surfing in Ghana and was in A&E in London, 200 miles away at the same time (Air Moroc had lost her luggage too, I guess I was trumped in that regard). I didn’t say anything, obviously, what with the house sale, my ex being her mother, and my reputation for always bringing the subject back to me… you couldn’t make this shit up, I said about the luggage.

And then, on the way home from the hospital, another email – Ben, the producer of the My Macondo, sends me an email with a link to a left-leaning website (remember those) and an article on the bad business of bananas – factual, shocking, and dryly written. I think he sent the email as a rebuke. I think he thinks I’ve been too busy selling the film, not saying what it’s about. True, I think.

Here’s a link to the article. You can see how bad the banana business is, and it’s still going on today, with America and now China vying for influence and profit at the expense of ordinary poor people.

Look David, in case you never got to see my film in the nineties, Ben would like you to know that My Macondo points a finger at America’s brutal presence in Latin America and the corporate imperialism of The United Fruit Company.

My Macondo investigates a strike of banana workers in 1928 near where Márquez was born, which ended in a terrible massacre, a strike and massacre that also appears in ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’. We talk to living witnesses and make a record of an important event in Colombian history that history tried to bury.

My Macondo is about some serious stuff and has important things to say, but it’s also fun and a little odd, as first films often are… and it has (I’m selling again) a rare and surprising interview with Gabriel Garcia Márquez and we find the actual village ‘Macondo’ which looks nothing like the one on Netflix or the one imagined in the book – but then imagination is personal when it comes to book reading, and that’s the point of the film if you get what I’m saying… and if you don’t, then you’ll be able to watch the film once the grading is done and the book I’m writing to accompany the film is finished.

Are you wondering about the title of this Substack-thingy, ‘Baths are for the filthy English’?

The story goes that when I met Márquez in Mexico City to do the interview for the film, he refused to believe I was the director. He said I was too young and too spotty (I was). He called me ‘the boy’. He then said with a twinkle in his eye, the same twinkle my mother had, another odd coincidence, that he’d never understand the English and how they bathed in filthy water for hours instead of taking a shower. When I lied and told him I hated clean water and only washed in pond water, he looked like he almost believed me. I told him I liked to swim wild because I was half Moari and half Viking. None of it was true, but we got on well after that. It felt good to pull the rug from a magical realist.

I hope you appreciate the story, David.

Bye for now, and bon voyage.

You meant so much to me, and I hope you like the film when it’s finished.

See you next week, perhaps.

Dan

UPDATE

I got an email from Dave just now – the other Dave – to say he’d made a ‘technical pass’ on the colour grade -from beginning to end. Dave Smith teaches with me at the Northern Film School in Leeds, in the UK. Thank you Dave!

Here is a picture of Dave showing me how difficult it is to grade my film… every shot is different from the one before and the one after - which is not normal, he says. It was a crazy shoot, I tell him, the mental Fuji 16mm film stock, and maybe the neg was bashed about in my attic, it was up there for thirty years. No, he says.

The grade is a first pass. There is more to do. More of My Macondo next week.

When I was little I would eàrnestly say I was half French, half Welsh and half English. I still somehow believe it.

But you ARE half Maori/half Viking, surely?